Broker Business Issue #5, 2020

December 16, 2020

New Unimutual Board Member – Andrew Flannery

February 20, 2021How did the pandemic impact Australia and what changes are set to last?

One could argue that the greatest cost of the pandemic in Australia is the 909 lives lost to date and the impacts on those families. Unfortunately, the human and societal costs have not stopped there, with job losses putting households under financial pressure, and mental health and well-being becoming of increasing concern, often associated with isolation and financial stressors.

In Unimutual’s COVID-19 FAQ article published back in July last year, we posed the question; What will life look like at the macro level after the lockdowns are relaxed?

Much has changed in the past 12 months, and while only time can tell what the future holds, many of our new ways of living and working are set to stick around.

We look back at the year past; how life changed for Australians, how well we adapted to rapidly changing circumstances, where we are now, and what will likely never go back to normal.

- How did daily life change for Australians?

- How well did we respond to the crisis?

- Work will be different for the foreseeable future

- We’re coping better and there’s a sense of new normal

- While the Australian economy is on track for a bounce back, the outlook for tertiary education is more dire

- The future of manufacturing and opportunities for tertiary education

How did daily life change for Australians?

People respond to pressure and adversity in different ways – 2020 saw both the best and the worst of people.

Panic buying was a feature of March and April 2020 (and again recently in Perth) with toilet paper, rice, and pasta high on the list of desirable items. On occasion, push turned to shove in the toilet paper isle and tempers flared. Hand sanitiser became another highly sought-after commodity.

We learned to respect personal space by social distancing and most Australians were compliant with Government directives.

Personal hygiene became a buzz word, and we saw a change in behaviour with frequent handwashing (hopefully an everlasting habit). Interestingly, the 2020 winter influenza season had one of the lowest mortality rates for many years with only 36 deaths recorded during 2020 compared to 430 in the same period during 2019. There were no deaths since April 2020. Authorities put this down to improved and regular handwashing, social distance, reduced community interaction and more people getting the flu shot.

For many workers, it was a quantum shift from being in the office full time to being forced to work from home. Some relished the opportunity, others found the new work arrangements challenging. For some, going to the office was a necessary division between home and work, and not having that routine blurred the psychological line between feeling that a day’s work had been done and not.

We learnt that it didn’t matter whether you were sitting at your office desk or at home – we could still effectively interact and conduct our business. Some took that a step further, moving from city locations to rural and regional areas.

When we did venture into the office, things were different with QR codes, capacity limits in offices, meeting rooms and elevators, and sanitising protocols.

Those in the higher education sector experienced a mix of working from home or in the office, depending on the nature and extent of local restrictions. Employment uncertainty was a stress many had to deal with. As revenue plummeted due to reductions in international student numbers; both forced and voluntary redundancies became a reality.

During periods of local lockdown and individual “slow down”, local communities tended to band closer together and the sense of community grew stronger. Shopping for the elderly, stopping to have a chat and checking on the well-being of others were reminiscent of a by-gone era.

During periods in between lockdowns the public transport commute was an interesting experience, with plenty of seats available. There were official rules regarding seating arrangements, but also an unwritten commuter etiquette. If anyone coughed, heads turned.

A range of different pressures adversely impacted the mental health of some people. These pressures ranged from economic hardship resulting from job losses, reduced corporate revenue and performance to a lack of social interaction, feelings of isolation and general anxiety.

How well did we respond to the crisis?

Australia as a country adapted reasonably well to the crisis. We recognised the threat, took the threat seriously, and devised and refined risk controls to manage the risk. We shut down international borders relatively quickly, limited arrival numbers, quarantined arrivals for the duration of their incubation periods and monitored and tested them. We largely prioritised public health over economic outcomes and decision makers took the advice of health professionals, making decisions based on science rather than political outcomes. Each state adopted a different stance on the balance between public health and economic impacts; only time will tell which strategy produced the best longer-term result.

Just like the 1919 Spanish flu pandemic, there were public education campaigns and mask wearing became commonplace in some states. One significant difference between 1919 and 2020 was the technology available to disseminate public information, stay connected with family, friends, and colleagues, and to track and trace the spread of the virus in the community.

From a pandemic risk management perspective, there were a raft of public health risk control measures – from border controls and community infection containment measures, to isolation controls for “high risk” groups such as aged care residents. Clusters of community transmission saw reasonably swift government intervention, including tracking and tracing of individuals and their contacts, genomic profiling, community notification and localised lockdowns as appropriate.

There were, however, several control failures. Early on, the docking and release of passengers from the Ruby Princess cruise liner due to miscommunication between government departments saw the virus leak into the NSW community, resulting in the impetus for the first lockdown in NSW. The most notable control failure was the Victorian hotel quarantine saga where poorly trained contract security guards did not adequately enforce isolation protocols. The failure to appropriately isolate guests from each other and the broader community, coupled with patchy testing, tracking and tracing thrust Victorians into an extended lockdown, isolating them from every other state as borders closed. The human, social and economic consequences of rapid community spread were severe.

The other noteworthy control failure was that of international flight crews and diplomats who were permitted to “self-isolate” and subsequently released variant strains into the community.

Work will be different for the foreseeable future

A KPMG review of remote working mirrors what we all inherently know; that there has been a rapid and large-scale shift across many industries towards working remotely; that organisations are investing in remote working technology and infrastructure, and the popularity of virtual communication platforms has surged.

The future of work will no doubt be a blend of office based and remote working as companies take a cautious approach to a fragmented vaccine roll out.

Nearly a year after governments first imposed lockdowns to contain the virus, there is a growing consensus that more staff will in the future be hired remotely, work more from home, and have an entirely different set of expectations of their managers.

KPMG predicts that remote working (both part-time and full-time) will continue to rise across all industries including financial services and the public sector, which have typically been office-bound and challenged by remote working at scale.

The 9-5 model seems dead and work success in the future will be measured by outcomes rather than input.

We’ve also experienced a decentralisation of the workplace. An Infrastructure Australia report has found the move to regional Australia by city workers will be semi-permanent, with about one in 10 people surveyed having relocated during the coronavirus pandemic, mostly to regional areas. The report estimates that four million employees have been working from home since March 2020, representing 30 per cent of the total workforce, with a third of that group likely to remain working remotely.

We’re coping better and there’s a sense of new normal

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics report suggests that we’re beginning to cope better in this new normal. The results from the November 2020 survey showed that around one in five (21%) Australians experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress – down from 46% in the August 2020 survey.

Women were more likely than men to have experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress (25% compared with 16%), and younger Australians (aged 18 to 34 years) experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress more commonly than older Australians.

We are also being more cautious, following government advice. Almost all (96%) respondents took one or more precautions in the previous week because of the spread of COVID-19, including washing hands or using hand sanitiser regularly (93%), keeping a physical distance from people (80%) and wearing a facemask (52%).

The survey also showed that the shift to online transcends work and study. One in three (33%) Australians reported they prefer to do more shopping online than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

One in seven (15%) people reported life had already returned to normal, compared with one in ten (10%) in July 2020. The most common aspect of life Australians wanted to continue after the COVID-19 restrictions ease was spending more time with family and friends (37%).

Check out the results from the latest ABS survey here.

While the Australian economy is on track for a bounce back, the outlook for tertiary education is more dire

We are yet to see how sovereign debt pans out across the globe, with governments pumping billions if not trillions of dollars into support packages for business and individuals to keep their economies ticking over. Vaccinations are reported by numerous economists to hold the key to economic recovery both locally and globally.

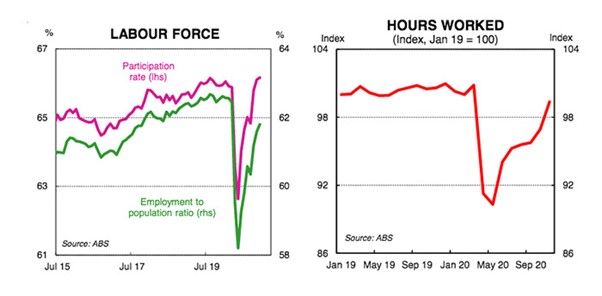

The CBA’s view is that the Australian economy is now well on track for a V-shaped rebound and for Australia’s labour market — a critical metric for economic health — the proof is in the (chart) pudding:

Data for Australia’s labour market tells a V-shaped story. (Source: CBA)

For CBA economist Gareth Aird, the employment rebound is one of multiple factors that point to a strong year of growth in 2021. On the health side, the nation is largely COVID-free (for now) and vaccine rollouts will commence in February or March. “In short, the Australian economy will have clear air once the rollout is complete and the very thing that has been holding the economy back will no longer be an issue,” Aird said.

He also notes that in the wake of the pandemic — consumer confidence surged to a 10-year high and with job losses contained, it meant more Aussies maintained their earning power while pandemic restrictions curtailed household spending, estimating that Australians saved around $125bn, equivalent to six per cent of GDP.

The Australian share market has been on a roller coaster responding to developments in the US, Japanese and European markets as investors become more cautious on fears of overvalued stocks and the lingering economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as second and third waves of infection ripple around the world.

The insurance industry has seen the continuation of a harder market as available capacity and investment returns remain subdued. One of the biggest issues arising from COVID for the industry to deal with is the fallout from BI claims made by many SME’s which may see insurers pay claims estimated in the 10’s of billions of dollars.

In the United Kingdom, regulator the Financial Conduct Authority moved to address the issue earlier this year by launching its own test cases to resolve whether insurers are liable under 21 different policy wordings. In September, the UK’s High Court ruled that in most cases the insurers were liable.

On the tertiary education front, Universities Australia, which represents the country’s 39 universities, calculated at least 17,300 jobs were shed from Australian campuses in 2020 – slightly lower than the 21,000 jobs it estimated were at risk in April. The figures comprise full time and casual positions.

It found universities’ operating revenues fell 4.9 per cent, or $1.8 billion, compared with 2019 figures, and predicted a further $2 billion decline this year.

Further, UA estimates that the sector will lose A$16 billion by 2023 and A$18 billion by 2024. Strategic plans and forward capital and operating budgets will need to account for these anticipated revenue reductions. Some institutions may be in budget pain for many years to come.

The future of manufacturing and opportunities for higher education

COVID-19 has brought the importance of Australian supply chains to the fore. As overseas supply chains came to a halt, industries here were significantly impacted by depleted supplies, prompting the government to consider an initiative that could sustain local manufacturing.

The $1.5 billion Modern Manufacturing Strategy was announced in the 2020-2021 federal budget. The Australian government is also providing a further tax incentive that will write off the value of assets for businesses, with more information yet to be released; perhaps there might be something in this for universities as well.

In a Sydney University press release, Professor Stefan Williams, Head of the School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering, says that modern manufacturing will require skills in a variety of fields, such as nano-technology and aerospace engineering. “We see great potential in the future of advanced manufacturing,” said Professor Williams.

“We are working closely with industry partners in a diverse range of areas including in the aerospace, biomedical, defence, energy and robotics sectors.

“The University of Sydney has recently invested heavily in the establishment of the Sydney Manufacturing Hub, a new Core Research Facility that will provide our staff and students with access to state-of-the-art manufacturing capabilities that will further accelerate our research in this area.”

Clearly, advancement in robotics and 3D printing, streams of research already well established on many university campuses, are an opportunity not to be missed.

The opportunities around advanced manufacturing are not lost on the University of South Australia either, who recently formed a working group of defence primes, SMEs, and government representatives to gain insights into the impact of COVID-19 on the local industry and develop strategies to drive the resurgence of high-end manufacturing.

The other area of university research which presents significant advanced manufacturing opportunity for the sector is climate change adaptation technology. The WEF’s Global Risk Report 2021 ranks climate change and environmental risks as some of the greatest challenges on the global risk horizon.

There’s a great synergy between advanced manufacturing and producing work ready graduates. La Trobe University vice-chancellor John Dewar says the sector is ready to participate in preparing the nation’s future workforce.

Download a pdf copy of this article here.

To read the latest checklists, forms and procedures, please visit our website here.

To subscribe to receive our checklists, forms and procedures or other Unimutual updates, please send your details to service@unimutual.com.au follow us on LinkedIn for notifications.